Menu

Menu

Posted: July 7, 2023

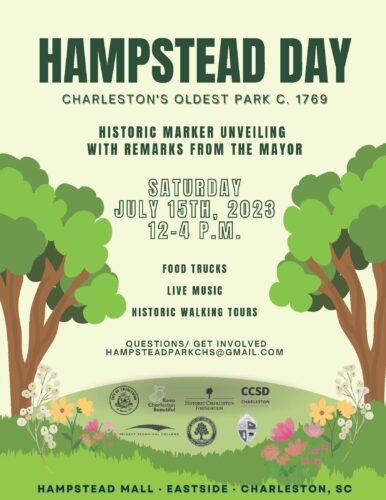

On Saturday, July 15, Historic Charleston Foundation is proud to support Hampstead Day. Recently, HCF sponsored the installation of a new Historic Marker for Hampstead Village and on July 15, Mayor Tecklenberg will unveil the new marker at this community event, free and open to the public. Join Historic Charleston Foundation and our friends Keep Charleston Beautiful, Charleston Parks Conservancy and other amazing organizations on Saturday, July 15 from 12 – 4 pm for this community event complete with food trucks, live music and historic walking tours. Do you have questions about this event? Contact [email protected]

On Saturday, July 15, Historic Charleston Foundation is proud to support Hampstead Day. Recently, HCF sponsored the installation of a new Historic Marker for Hampstead Village and on July 15, Mayor Tecklenberg will unveil the new marker at this community event, free and open to the public. Join Historic Charleston Foundation and our friends Keep Charleston Beautiful, Charleston Parks Conservancy and other amazing organizations on Saturday, July 15 from 12 – 4 pm for this community event complete with food trucks, live music and historic walking tours. Do you have questions about this event? Contact [email protected]

Event highlights!

How much do you know about Hampstead Village or its rich history? In 2019, Charleston County Public Library’s podcast, The Charleston Time Machine, explored the expansive (and often forgotten) history. Read more, below:

The neighborhood of Hampstead within the City of Charleston is one of the oldest and least-interpreted of the peninsula’s historic boroughs. Today, Hampstead Village is considered the heart of Charleston’s “Eastside”, the boundaries of which have changed over the years, but generally, it describes “the swath of peninsular Charleston bounded on the south by Mary Street, on the west by Meeting Street, on the east by the Cooper River, and continuing northward to about Huger Street. If you’re using Google Maps within this area, your smart phone might say that you’re in Radcliffeborough, or Wraggborough, or Elliottborough, or another one of Charleston’s identifiable historic neighborhoods. But Google is mistaken. Charleston’s generic “Eastside” has a deep history and identity that most of the community has forgotten over the past sixty years.” Butler, Charleston Time Machine.

The land that became known as Hampstead was once part of a large tract of land north of Charleston, first given to Richard Cole in the summer of 1672. This property stretching from the Ashley to the Cooper River, was divided many times over successive generations, but retained its rural character. In the late 1760s, a large pasture within that land was known as Austin Field, and its owner, Mr. George Austin, sold his field to Henry Laurens in 1769. After acquiring additional acres to the north, Laurens hired a surveyor to divide the tract into building lots and to lay out an orderly grid of streets. In November, 1769, Henry Laurens began marketing his property to the public as “the Village of Hampstead” a residential development.

Henry Laurens named the central east-west street for Christopher Columbus, and the central north-south street for that mariner’s greatest discovery, America. Both of those principal streets were fifty feet wide, while the remaining nine streets were all forty feet wide. Three streets were named for celebrated men of English history. Drake Street was named for the explorer, Sir Francis Drake. Amherst Street was named for the British commander of North American forces during the recent French and Indian War (1756–1763), General Jeffery Amherst. Wolfe Street (now misspelled “Woolfe”) was named for the fallen hero of the 1759 Battle of Quebec, General James Wolfe. Two of the streets were named for bloodlines of the English royalty. Nassau Street was named for King William III, of the House of Nassau, while Hanover Street was named for the successive King Georges and the House of Hanover. The four remaining streets have more mundane names. Reid Street was named for James Reid, the man who owned property along the southwest corner of Hampstead. Similarly, Blake Street, at the northern edge of the village, bounded on land owned by the Blake family. South Street was apparently so named simply because it marked the southern limit of the village. A short stub of a street at the northeast corner was originally called Bull Street, but later became Cooper Street. – Butler, Charleston Time Machine

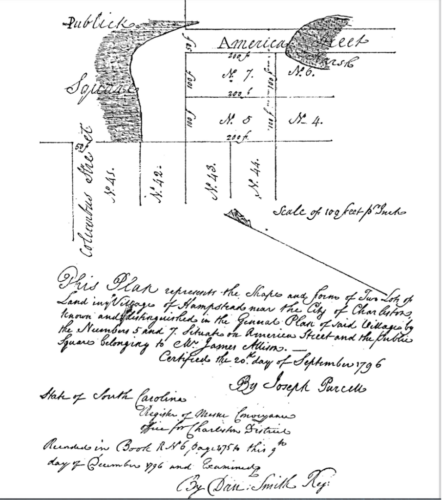

A 1796 plat by Joseph Purcell showing part of Hampstead Mall

The 1769 survey of Hampstead laid out 140 rectangular building lots, each nearly half an acre in size and at the intersection of Columbus and America Streets, the plan reserved 450 feet on each side, or roughly four and a half acres, to develop a public square. Early purchasers decided to preserve the square as a public green and although it’s now four squares instead of one, it’s still known as Hampstead Mall, now the oldest public green space in Charleston.

As Charleston entered the early 1770s, tensions between the American colonies and Britain increased and economic growth slowed. The British Army descended on the peninsula of Charleston in early May 1779. The American forces defending the town were not prepared; fortifications along the northern boundary of town were incomplete, and the new houses in the village of Hampstead stood between the city and the approaching enemy, blocking the view of the American defenders. On May 9th, 1779, South Carolina Governor John Rutledge issued an order to raze Hampstead and only gave property owners a few hours to evacuate their possessions before the new residences were set ablaze and pulled down. Two days later, General Prevost and his army quietly retreated from the peninsula without firing a shot at Charleston. In 1780, American defenders built a small battery on the highest point in Hampstead Village, near the intersection of Drake and Blake Streets, called Hampstead Hill. Later, the British army captured Hampstead Hill and transformed it into an even larger fortification.

The City of Charleston was formally incorporated in 1783, creating a more robust system of government and law enforcement for the more populous neighborhoods located south of Boundary Street (created in 1769, now Calhoun Street). Following that act, the unincorporated area north of Boundary Street, generally called “the Neck,” soon acquired a reputation as a place of relative freedom beyond the reach of city government. Taxes were lower, fewer laws were enforced, and there was less government oversight in general. … Around the turn of the nineteenth century, Hampstead was home to a relatively diverse population, including affluent merchants and planters, middle-class tradesmen, free people of color, and enslaved day laborers. The absence of robust government oversight also attracted a variety of small shops, as well as larger commercial operations like ropewalks, slaughter pens, candle factories, and even a botanical garden. As political tensions between the United States and Britain increased to the brink of war in the early 1800s, however, the economy soured and growth stopped. When war was declared in the summer of 1812, the village of Hampstead was once again threatened with extinction. – Butler, Charleston Time Machine

The War of 1812 ended in the spring of 1815, making the new fortifications on private property confiscated by the government during a time of crisis, obsolete. In 1823, the property was subdivided into dozens of lots between two newly-created streets, Line Street and Shepherd (now spelled “Sheppard”) Street, and sold. In the late 1820s and early 1830s, the village of Hampstead bounced back as affluent property owners (who resided outside the village) continued to divide their land to build rental tenements. Business moved into the neighborhood, skilled and unskilled laborers, both black and white, enslaved and free, soon formed the majority of village’s population and large numbers of European immigrants (mostly Irish and German), joined the neighborhood in the 1840s and 1850s. At the time, Hampstead and surrounding neighborhoods comprised what was known as “the Neck”.

The City of Charleston, in late 1849, annexed a large swath of “the Neck” resulting in Hampstead Village and several other neighborhoods officially incorporated into the city in 1850, making Mount Pleasant Street Charleston’s new northern boundary. The act of annexation did not result in many neighborhood changes; “the streets remained unpaved, sandy thoroughfares, and municipal utilities like running water, sewerage, and street lights, would not arrive for many more decades” Butler, Charleston Time Machine.

Cigar Factory

The Civil War decimated Charleston’s economy and infrastructure. Following The Civil War, the working-class, mixed-race Hampstead Village became increasingly diverse as large numbers of formerly-enslaved people moved from the rural plantations for a new life in Charleston. The Charleston Manufacturing Company constructed a massive cotton mill facing East Bay Street in 1882. Built on the southern part of Hampstead Hill, the cotton factory became a cigar factory in 1912, and still stands, today.

Between the Federal Censuses of 1950 and 1960, the neighborhood’s population shifted from being predominantly white to predominantly African-American. That demographic transition did not happen overnight, of course. That unprecedented change worried many conservative white politicians, whose prejudiced opinions served to further isolate and stigmatize the neighborhood.[14] In the wake of census polling in 1960, the City of Charleston re-designated the white-only playground at Hampstead Mall to be a “colored playground.”[15]

In the early 1960s, many people in the Charleston area began to view the Hampstead neighborhood as a distinct, isolated, and undesirable enclave within a larger, more homogenous community… and that discriminatory mentality quickly eroded its two centuries of identity as a mixed-race, working-class village. As the neighborhood’s overall population shrank, many of its modest but historic homes became vacant, boarded-up eyesores… Many homes still lacked modern water and sewer facilities, and there was little economic incentive to modernize declining properties.[16] Politicians, neighbors, and the police began to complain about the increase in crime and delinquency in Ward No. 9, located on the east side of the Charleston peninsula.[17] The name “Hampstead” gradually disappeared from the Charleston lexicon in the early 1960s, as the chorus of complaints about the “East Side” grew louder. By 1965, the city was using Federal grant money to help reduce juvenile crime in Charleston’s “East Side,” and by 1966 there was a grassroots “Eastside Development Council” campaigning to improve the neighborhood’s economic health.[18] Stay away from the East Side, parents told their children. Help us improve the East Side, residents begged the city. – Butler, Charleston Time Machine

Historic Marker #1077

Black artisans on the Eastside created a community that residents cherished and Blake Street is the famed Phillip Simmons’ home and workshop. For the better part of a century, Simmons was one of the most celebrated blacksmiths in the world, making iron rails, gates, and fences for countless homes and businesses across the Charleston area. Simmons was a beloved member of the Eastside community, opening his home to school groups, gifting money to young high school graduates, and avidly participating in his church. In 1946 – the East Side was witness to major activism and historic labor strikes. “The Cigar Factory in 1946 and the hospital at the medical college in 1969 were both the sites of major labor strikes organized by the Black workers…. The strike on its own would not have been successful without the work done by Black community members, like those on the Eastside who applied pressure to the hospital, and its supporters.” Merida, Transforming Hampstead Village.

A news article published in the summer of 1969 described Charleston’s Eastside neighborhood as “the most densely populated area per square block in the State of South Carolina,” and among the poorest as well. In the late twentieth century, as the Charleston-metro area expanded, the city’s Eastside continued to struggle. New residents, increasing numbers of tourists, and commercial investment—especially after Hurricane Hugo in 1989— has transformed Charleston into an increasingly desirable travel destination, but the economic benefits has largely bypassed the Eastside.

In recent years, gentrification has posed a major threat to Eastside residents. While it was considered undesirable by privileged people in the past, it is a magnet for people looking to relocate in Charleston in no small part because of its relatively cheap property value. … As Charleston continues to grow and evolve, communities like the Eastside need to be protected as the cultural gems that make the city of Charleston so unique. In the same way that Black Hampstead Villagers chose to transform the Eastside and we should all choose to celebrate and protect its legacy as a haven for Black Charlestonians. – Merida, Avery Research Center, Transforming Hampstead Village

There have been many heroes campaigning for the improvement of the Eastside neighborhood over the past sixty years, and local government has not been completely blind to the issues at hand. … Identity, both personal and communal, is an important and necessary part of empowerment. Perhaps by reclaiming this neighborhood’s largely-forgotten historic name, Hampstead, and its diverse heritage, we can muster the strength to move forward together and overcome the legacy of discrimination and disparity that gave rise to the name “Eastside” nearly sixty years ago. – Butler, Charleston Time Machine

Research and information adapted from Nic Butler, PhD and The Charleston Time Machine, “Episode 131, Hampstead Village: The Historic Heart of Charleston’s East Side” October 18, 2019. Read full article from Charleston County Public Library HERE. Additional information and research courtesy of the Avery Research Center, Mateo Merida, Transforming Hampstead Village, May 2023

Thank you for this surprisingly detailed account of Hamptead’s history. I’ve learned so much about “the Neck.

Re Hampstead Village article

Love knowing that a botanical garden once existed on east side of Charleston. Maybe that’s what the 64-acre former port site should become—affordable housing for people working downtown, surrounded by a world-class botanical garden and public playgrounds, all built to standards informed by the Dutch Dialogues and latest rising sea level research. Thank you for all you do!